WHICH SPIRITUAL DISCIPLINES?

By Ken Silva pastor-teacher on Dec 18, 2009 in AM Missives, Contemplative Spirituality/Mysticism, Current Issues, Dallas Willard, Richard Foster, Southern Baptist Convention, Spiritual Formation

The following look at The Dangers of Spiritual Formation and Spiritual Disciplines is taken from a review by Bob DeWaay, pastor of Twin City Fellowship, of the book The Spirit of the Disciplines by Dallas Willard:

The following look at The Dangers of Spiritual Formation and Spiritual Disciplines is taken from a review by Bob DeWaay, pastor of Twin City Fellowship, of the book The Spirit of the Disciplines by Dallas Willard:

The spiritual disciplines that are supposedly necessary for spiritual formation are not defined in the Bible. If they were, there would be a clear description of them and concrete list. But since spiritual disciplines vary, and have been invented by spiritual pioneers in church history, no one can be sure which ones are valid. Willard says, [W]e need not try to come up with a complete list of disciplines. Nor should we assume that our particular list will be right for others.” [1] The practices are gleaned from various sources and the individual has to decide which ones work the best. Willard lists the following: voluntary exile, night vigil of rejecting sleep, journaling, OT Sabbath keeping, physical labor, solitude, fasting, study, and prayer. [2] Willard then lists “disciplines of abstinence” (solitude, silence, fasting, frugality, chastity, secrecy, sacrifice) and “disciplines of engagement” (study, worship, celebration, service, prayer, fellowship, confession, submission).[3]

Willard offers a discussion of each of these, citing people like Thomas Merton, Thomas a Kempis, Henri Nouwen, and other mystics. We are told that practices like solitude and silence are going to change us, even though the Bible does not prescribe them. Willard writes, “This factual priority of solitude is, I believe, a sound element in monastic asceticism. Locked into interaction with the human beings that make up our fallen world, it is all but impossible to grow in grace as one should.” [4] So if we cannot grow in grace without solitude, how come the Bible never commands us to practice solitude? The same goes for many other items on Willard’s list.

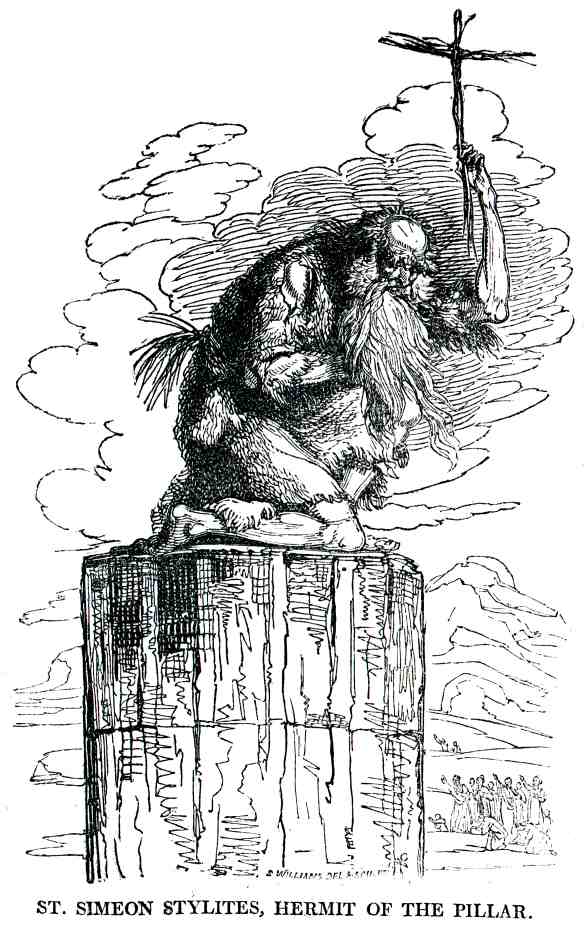

Willard tells us that the list of disciplines he provides is not exhaustive. Others can be pragmatically determined. He says, “As we have indicated, there are many other activities that could, for the right person and upon the right occasion, be counted as spiritual disciplines in the strict sense stated of our previous chapter. The walk with Christ certainly is one that leaves room for and even calls for individual creativity and an experimental attitude in such matters.” [5] However, there is a serious problem with Willard’s logic here. Earlier he rejected such practices as self-flagellation, exposing the body to severities including being eaten by beetles, being suspended by iron shackles, and other means of severely treating the body in order to become more holy.[6] Willard rejects these on the following grounds: “Here it is matter of taking pains about taking pains. It is in fact a variety of self-obsession—narcissism—a thing farthest removed from the worship and service of God.” [7]

Willard had admitted that there is no clear list of the disciplines and that each person might choose different practices through pragmatic means. This does not give sufficient ground for rejecting such practices as self-flagellation. So Willard resorts to arguing that those who do such things have bad motives. But he cannot really know their motives, perhaps they determined that these practices “worked” using the same means Willard offered. If pragmatic tests are the means of determining which practices are valid, and if these people feel closer to God and more like Christ through their practices, then Willard has no valid way of rejecting their practices. Having no valid argument, he resorts to an invalid ad hominem argument.

He cannot have it both ways. Either God’s Word determines both how we come to God and how we grow in grace, or humans determine these things by pragmatic means. Willard has chosen the later. But then he steps in and tells us that some practices are wrong, even though they fit his own criteria for validity. If a person feels that sleeping in a tiny stone crevice with all the heat being sucked out of his body makes him more spiritually disciplined, then who is to say that is wrong? Had he been willing to submit to the authority of Scripture, Willard could have refuted these practices based on Colossians 2:21-23.

Even though decrying some of the excesses of monasticism, Willard is fond of the monastics and thinks that the Reformation left us with no practical means of spiritual growth. He says, “It [Protestantism] precluded ‘works’ and Catholicism’s ecclesiastical sacraments as essential for salvation, but it continued to lack any adequate account for what human beings do to become, by the grace of God, the kind of people Jesus obviously calls them to be.” [8] This is simply false. Luther believed in means of grace that God has provided all true believers that they might grow in the grace and knowledge of the Lord. [9] The difference is that means of grace are what God has provided for all Christians for all ages and they are determined by God, not man. These are revealed in the Bible. Spiritual disciplines are man-made, amorphous, and not revealed in the Bible; they assume that one is saved by grace and perfected by works.

Paul wrote, “Are you so foolish? Having begun by the Spirit, are you now being perfected by the flesh?” (Galatians 3:3). Paul rejected the idea that we are saved by grace and perfected by works. We are saved by grace and we grow by grace. Willard seems to miss this point. Here is how he views it: “The activities mentioned—when we engage in them conscientiously and creatively and adapt them to our individual needs, time and place—will be more than adequate to help us receive the full Christ-life and become the kind of person that should emerge in the following of him.” [10] Elsewhere he suggests that growth comes through human will power: “The entire question of discipline, therefore, is how to apply acts of the will at our disposal in such a way that the proper course of action, which cannot always be realized by direct and untrained effort, will nevertheless be carried out when needed.” [11] It is hard to see how this is anything other than “being perfected by the flesh” which Paul said was impossible.

The Reformation understanding of means of grace was that they were God’s gracious means of working in a person of faith’s life. What ever is not of faith is sin. Even the Word and sacraments as Luther understood them were of no avail unless they were received in faith. No works righteousness could be tolerated. Willard’s approach is works oriented and man-centered; it was created by spiritual innovators who mostly did not find their practices in the Bible.

The article by Bob DeWaay, from which this was adapted, appears in its entirety at Critical Issues Commentary right here.

________________________________________________________________________________

Endnotes:1. Dallas Willard, The Spirit of the Disciplines, Understanding How God Changes Lives, (HarperCollins: New York, 1991), 157.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., 158.

4. Ibid. 161, 162.

5. Ibid. 190.

6. Ibid. 142-144.

7. Ibid. 144.

8. Ibid. 145.

9. See Bob DeWaay, “Means of Grace” in Critical Issues Commentary, Issue 84, Sept./Oct. 2004. http://cicministry.org/commentary/issue84.htm

10. Willard, 191.

11. Ibid. 151, 152 emphasis his.

See also:

CONTEMPLATIVE SPIRITUALITY OF RICHARD FOSTER ROOTED IN THE EASTERN DESERT AND THOMAS MERTON

SPIRITUAL FORMATION IS PIETISM REIMAGINED

DISCIPLINES TO DECEPTION IN SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONVENTION

THE TERMINOLOGY TRAP OF “SPIRITUAL FORMATION”

DONALD WHITNEY AND EVANGELICAL CONTEMPLATIVE SPIRITUALITY/MYSTICISM