ATTEMPTS AT THE IMPOSSIBLE

By Ken Silva pastor-teacher on Oct 23, 2010 in Current Issues, Features, Quotes

I may, however, venture to express the opinion, that the evangelical brethren in the Association have acted with much kindness, and have shown a strong desire to abide in union with others, if such union could he compassed without the sacrifice of truth. They as good as said—We think there are some few great truths which are essential to the reception of the Christian religion, and we do not think we should be right to associate with those who repudiate those truths. Will you not agree that these truths should be stated, and that it should be known that persons who fail to accept these vital truths cannot join the Association?

I may, however, venture to express the opinion, that the evangelical brethren in the Association have acted with much kindness, and have shown a strong desire to abide in union with others, if such union could he compassed without the sacrifice of truth. They as good as said—We think there are some few great truths which are essential to the reception of the Christian religion, and we do not think we should be right to associate with those who repudiate those truths. Will you not agree that these truths should be stated, and that it should be known that persons who fail to accept these vital truths cannot join the Association?

The points mentioned were certainly elementary enough, and we did not wonder that one of the brethren exclaimed, “May God help those who do not believe these things! Where must they be?” Indeed, little objection was taken to the statements which were tabulated, but the objection was to a belief in these being made indispensable to membership. It was as though it had been said, “Yes, we believe in the Godhead of the Lord Jesus; but we would not keep a man out of our fellowship because he thought our Lord to be a mere man. We believe in the atonement; but if another man rejects it, he must not, therefore, be excluded from our number.”

Here was the point at issue: one party would gladly fellowship every person who had been baptized, and the other party desired that at the least the elements of the faith should be believed, and the first principles of the gospel should be professed by those who were admitted into the fellowship of the Association. Since neither party could yield the point in dispute, what remained for them but to separate with as little friction as possible? To this hour, I must confess that I do not understand the action of either side in this dispute, if viewed in the white light of logic. Why should they wish to be together? Those who wish for the illimitable fellowship of men of every shade of belief or doubt would be all the freer for the absence of those stubborn evangelicals who have cost them so many battles.

The brethren, on the other hand, who have a doctrinal faith, and prize it, must have learned by this time that whatever terms may be patched up, there is no spiritual oneness between themselves and the new religionists. They must also have felt that the very endeavor to make a compact which will tacitly be understood in two senses, is far from being an ennobling and purifying exercise to either party. he brethren in the middle are the source of this clinging together of discordant elements. These who are for peace at any price, who persuade themselves that there is very little wrong, who care chiefly to maintain existing institutions, these are the good people who induce the weary combatants to repeat the futile attempt at a coalition, which, in the nature of things, must break down.

If both sides could be unfaithful to conscience, or if the glorious gospel could be thrust altogether out of the question, there might be a league of amity established; but as neither of these things can be, there would seem to be no reason for persevering in the-attempt to maintain a confederacy for which there is no justification in fact, and from which there can be no worthy result, seeing it does not embody a living truth. A desire for unity is commendable. Blessed are they who can promote it and preserve it! But there are other matters to be considered as well as unity, and sometimes these may even demand the first place. When union becomes a moral impossibility, it may almost drop out of calculation in arranging plans and methods of working.

If it is clear as the sun at noonday that no real union can exist, it is idle to strive after the impossible, and it is wise to go about other and more practicable business. There are now two parties in the religious world, and a great mixed multitude who from various causes decline to be ranked with either of them. In this army of intermediates are many who have no right to be there; but we spare them. The day will, however, come when they will have to reckon with their own consciences. When the light is taken out of its place, they may have to mourn that they were not willing to trim the lamp, nor even to notice that the flame grew dim. (Online source)

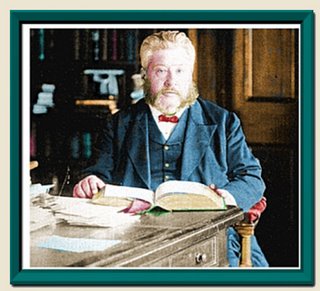

Charles Spurgeon